Nearly 6.5 million renter households were behind on rent by July of this year, and millions more had borrowed money or taken out loans to get by. No break is in sight, as housing market supply shortages mean home prices and rents will continue to rise.

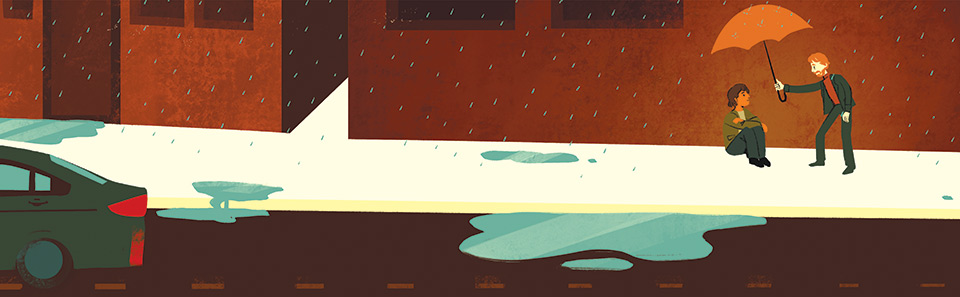

As COVID-19 and its variants continue to rage, social workers are working with impacted individuals and families, pushing for legislative relief and joining with partner organizations to help those at risk and bring about change in the lives of those who need it the most — including those who have no place to call home.

Unequal Impact

While widespread, impacts from the pandemic and its “economic fallout” have hit Black and Latino adults and other people of color harder. That reflects inequities in education, employment, housing and health care that have disproportionally affected people of color, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities stated. Households with children are experiencing especially high hardship rates as one in four adults have trouble covering expenses and one in three children living in renter households face food and/or housing hardships.

Evictions Rise

“Rent prices soared 9.2 percent in the first half of 2021, tripling the average pace and exceeding the pre-crisis trend,” and rises are expected to “keep climbing,” according to Business Insider. President Joe Biden staved off evictions, working with the CDC, which issued a temporary eviction halt on Sept. 4, 2020, that was extended multiple times — with a recent extension that was set to expire Oct. 3.

More Homeless

After earning his master’s degree in social work, Justin Behrens is CEO and executive director at Keystone Mission in Scranton, Pa. Since the virus hit, he has seen an increase in the homeless population of about 25 percent. He estimates in larger cities like Los Angeles and Chicago, the homeless populations may have grown 30 percent. He also has seen a difference in the people who currently are homeless in Scranton.

“Now it’s more people who never had a homeless problem before,” he said. “We always ask to hear their story. It’s our way of doing an assessment and finding out what their needs are.”

For example, Behrens said a gentleman in his mid-60s came in and asked, “What do I do?” He, his wife and their dog were living in their car. Never before homeless, the man did not know where to start or where to go.

“The biggest problem is the demand is high and we don’t have the resources to meet the demand,” Behrens said. He believes it’s “the tip of the iceberg, and it’s going to get worse. This is all across the country.”

Unfortunately, there is a stigma attached to being homeless, no matter the education, background and history of the person, he said. But there’s “Joe,” who has been homeless for seven years and never has used alcohol or drugs nor committed any crimes. And there’s “Billy,” who had been in college and ran out of money, and “they’re classified as a group with a stigma across the board,” Behrens said. “They’re just like you and me. They just have a bad situation in a bad time.”

His facility provides meals and offers some housing. Behrens said he has seen a 27.4 percent increase in the number of meals provided, and it’s happening across the country. There are ways for social workers to help, he said, and it’s best to partner with an agency. “The only way we’re going to change homelessness is working together as a whole. It’s the ‘everyone rowing the boat’ idea, and it brings a united front.”

You must work as a team, and communicate with other agencies, tell them what’s going on, and put the word out so all agencies are networking and everybody is working together. Find out where the funding is, where the gaps are, and build bridges across them, he said.

Don’t judge any individual and do not do an assessment, but get their story, Behrens said. “Like a detective, pick out clues, little nuggets, and find what happened in their lives. Listen to their story, and you can help make a change in their lives.”

Offering relief is very important. It is good to a point, but we need to transform lives — so at some point you have to start pulling back so they can move in the right direction, Behrens said.

When it comes to ballooning home and rental prices, social workers are some of the right people to address that, too, he said. “We have to get off our tails and get out there and advocate. We’re powerful. We know what to do and how to make change and how to help change someone’s life.”

“We know how to listen, and how to interpret what they say, and we know how to advocate,” Behrens added. “There’s no other profession that does all that.”

Housing First

If people have no home, how can they think about anything else?

Sam J. Tsemberis, a clinical and community psychologist, developed Pathways to Housing in New York City in 1992. The Housing First program he created is an evidence-based program with a “robust research evidence base” and is credited with success in helping homeless populations in the U.S., Canada, European Union, Australia and New Zealand. Tsemberis is CEO of the Pathways Housing First Institute and an associate clinical professor at UCLA in Los Angeles. He believes housing is a basic human right that “provides recovery-focused supports.”

Several randomized control trial findings show an 80 percent rate of housing stability with the Housing First program, he said, which is double the stability for traditional programs. The National Alliance to End Homelessness, in an April 2016 fact sheet, says the approach provides permanent housing that ends a person’s homelessness. That serves as a platform “from which they can pursue personal goals and improve their quality of life.”

Housing First programs operate across the United States, Canada, many European Union countries, Australia and New Zealand.

Create Change

In 1983, the Baltimore City Department of Social Services was created, said Jeff Singer, MSW, LCSW-C, an adjunct professor at the University of Maryland School of Social Work in Baltimore, where he also does outreach for the school and for City Advocates in Solidarity with the Homeless.

“People were coming in and applying for benefits, for help, and they were turned down because they were homeless,” he said. “No address, no benefits. So we began to address that. The department created a homeless unit, and the policy changed.”

People who applied would get help, and could, if eligible, receive public assistance, medical care, food stamps and a place to stay.

“In 1983, there were very few emergency shelters,” Singer said. “There were a couple of missions, religious facilities where you had to pray in order to stay.”

One of two in Baltimore housed about 200 people, and in a big meeting room where the Bible was taught, they had to stand one at a time and read a scripture written on the blackboard.

“Can you imagine the problem with that?” Singer asked. “One, there were people who couldn’t read; and two, there were people who weren’t Christian. So I began to organize a union.”

In the early 1980s, The Baltimore Homeless Union was formed, and “its slogan was Homeless Not Helpless. We had (badge-type) buttons made up” he said. On Thanksgiving in 1984, they notified the city and then took over a vacant school building because people had no place to stay. The next year, Singer said, the group told the city it was going to break into city-owned empty houses.

“We used a pry bar,” Singer said. “It helped a family. That worked out pretty well, so we took over some others.” The group lasted for about 20 years, he said.

Singer worked for 15 years at the Baltimore City Department of Social Services, then worked 25 years at Health Care for the Homeless, retiring after it had “its millionth patient visit with its 100,000th patient,” the university states on its website.

NASW-Maryland, in announcing Singer as the chapter’s 2010 Social Worker of the Year, wrote that his career “truly reflects the words service, advocacy and leadership.”

“I don’t think the causes of homelessness have changed,” he said. “Look at 1873, 1894, 1919 and 1933 — it’s all about people whose income isn’t sufficient to afford housing. It’s capitalism and certain rules you have to follow and the money you have to make.”

Right now, the country is in one of those times where prices go up higher and higher, Singer said, and public policy is a factor. “In the 1930s and 1940s, we built public housing — one of the best ways to prevent homelessness. Since Nixon’s time, we’ve stopped that funding, and now the need is greater. So I think the public policy solution is to invigorate the public housing sector.”

Housing vouchers are more expensive because landlords must make a profit, Singer said. Thirteen million American households are at risk of homelessness. Social workers can do something about that, he said — social workers and their allies can promote community land trusts. First, organize people whose housing is at risk and lobby their friends, politicians and families to advocate for more affordable housing and for community land trusts, where the community owns the land and the trust and people can buy or build houses on the land.

“One of the rules on that land is you can’t sell them for a lot more than you bought them for, then there’s no speculation, there’s no flipping,” he said.

Social workers also can advocate in state capitols and in Washington, D.C., for more public housing funded by the federal government. They can advocate for local housing authorities and housing trust funds instead of housing vouchers that enrich landlords.

What should the profession do? “Organize at the local level, organize on the statewide level and organize on the national level,” Singer said.

The National Low Income Housing commission, at nlihc.org, has an advocacy agenda and action steps, and the National Health Care for the Homeless Council, at nhchc.org, also offers information, he said, as do many other organizations. There is “probably not enough” information on the housing issue in social work schools,” Singer said. “When I started teaching, there was no course on housing policy, so I created one and now I teach it. It does help you understand why and what you can do about it.”

“Organization is the answer to most questions,” he added. “Before we can change something, we have to understand it.”

Data Needed

Since the country still is in the midst of the pandemic, it’s difficult to assess its impact on youth and others who are homeless because there is no data yet, said Benjamin F. Henwood, PhD, MSW, an associate professor at the Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, where he also is director of the Center for Homelessness, Housing and Health Equity Research. He is a co-leader of the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare’s Grand Challenge to End Homelessness and a member of the AASWSW Leadership Board.

“In some ways, the homeless number depends on where you are,” he said.

After the pandemic hit, the initial focus was on funding for sheltering people who are homeless. Then, since many people in California were living outdoors, there were indications that population was experiencing lower rates of COVID because social distancing is natural outside. But some outbreaks were seen and a lot of new funding came in to provide options for people, he said.

Henwood is a researcher, and said since the country still is in the midst of the pandemic and there is no hard data available yet, “there’s an unclear picture of where we are now,” although he has heard anecdotally it’s been a struggle to serve the homeless population.

“A lot of drivers of homelessness in youth are due to a lot of institutions that are not working well, and I imagine that’s due to the pandemic,” he said. “In general, I think the pandemic has put more pressure and stress on families. That’s not getting any better. It also could lead to more youth leaving a family environment. It’s just unknown at this point.”

The host home model, said Henwood, has helped some youth. That is where a young person stays in an extra room in someone’s home. Younger adults who identify as LGBTQ+ face slightly different issues, he said. “There are a lot who do ‘couch surfing,’ and rely on friends,” because they have no place to go, nowhere to sleep.

Overall, wealth and inequality gaps are increasing, Henwood said, and the thread through it all is racial injustice, which is inextricably linked to all challenges. “It’s all tied together, and that’s fundamental to what social work does.”

How to Help

Author David Elliot published a July 30, 2021, post for the Coalition on Human Needs titled The "Worst National Eviction Crisis In U.S. History?" How You Can Help.

Some takeaways:

- Immediate action is necessary, so everyone should write to their elected officials and demand an expansion of the housing voucher program. The current waiting list is from 28 months to up to five years in some areas.

- Anyone who knows someone struggling with rent, utilities and other costs or knows a landlord “trying to stay afloat,” emergency aid is available but the $46 billion Congress approved is “flowing out more quickly in some places than others.”

- People can visit the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau website to find out if they qualify and learn how to apply.

- Elliot quotes research from the National Low Income Housing Coalition that shows evictions between March 2020, when the pandemic began, and September 2020, when the first eviction moratorium was enacted. This resulted in more than 400,000 additional virus cases “and nearly 11,000 additional deaths.”