Social workers historically have been active in environmental issues, particularly advocating for populations who are negatively impacted by environmental injustices. As the climate crisis accelerates, social workers need to proactively engage with clients and communities and respond to the growing impacts of environmental changes, say social workers active in the field.

To aid in this effort, NASW presented a virtual forum in November called “Environmental Justice: Through the Social Work Lens.” It featured topics like ecosocial work, mental health and climate anxiety, and community organizing. The presenters agreed that all social workers can positively advance environmental justice.

Environmental Racism

Environmental racism refers to any environmental policy, practice or directive that negatively affects (intentionally or not) individuals, groups or communities based on race or color.

Natalie Moore-Bembry, Ed.D, MSW, LCSW, assistant professor at Rutgers School of Social Work, presented on this topic. She said institutionalized environmental racism is differential access to goods, services and opportunities by race.

“When you talk about environmental racism, it is perpetuated through our historical policies, laws and regulations that have long favored white residents over residents of minoritized populations,” she said. Those laws further impact zoning and housing in various cities.

Some examples of discriminatory zoning are the deliberate placement of toxic waste sites, municipal waste facilities, power plants, radioactive waste sites, landfills, incinerators, and contaminated wells in low-income neighborhoods that have high minority populations, Moore-Bembry said. In north Birmingham, Ala., for example, industrial pollution sites explicitly were located in Black neighborhoods.

Weak enforcement of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency policies and practices also have an impact. An example of this is the water crisis in Flint, Mich. “This is a crisis that has been going on for a number of years, but it is a direct result of the city, state and federal officials ignoring the pleas of the community when they complained (about) the discolored water,” Moore-Bembry said.

The other presenters on this topic also were from Rutgers School of Social Work: Christine Morales, MSW, assistant dean; and Mariann Bischoff, MSW, MS, LCSW, assistant professor.

Politics and the Environment

When it comes to addressing climate change issues, local, county, state and federal governments play an essential role.

Justin D. Hodge, LMSW, clinical associate professor of social work at the University of Michigan and chair of the Washtenaw County (Mich.) board of commissioners, explained how social workers can work with governments and organizations for climate justice. Hodge noted many challenges that local, county and state governments face, including childcare funding, blight, rising rent costs, and retaining young people to work in government.

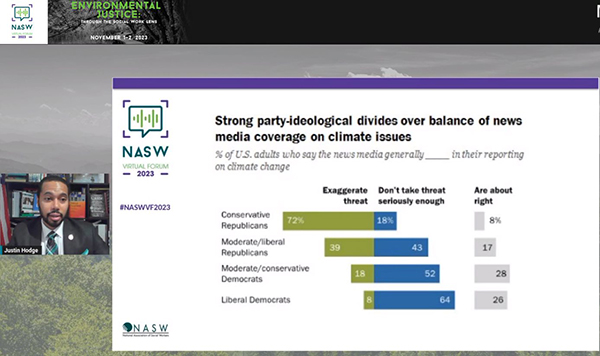

Some of these issues include immediate needs, which put topics like climate change low on the priority list, he said, adding that a strong party ideology divides the issue. Significant differences exist between people across the political spectrum on climate change and the role of scientists who study it.

“There are a number of people who feel the media overblows the issue,” Hodge said. “Then there are a number of people who don’t think it’s being talked about enough.”

A Patchwork of Climate Action Plans

He noted Washtenaw County has its own climate action plan. This is in addition to climate action plans from the University of Michigan and another from the city of Ann Arbor, which are in the county as well.

“In some ways it makes sense for each to have their own,” Hodge said. However, some of the goals overlap. All three entities have their climate crisis staff, and collaborations don’t always happen. “If you look at your communities across the country, you are likely to see a wide variety of action plans. That’s not always helpful.”

Part of the challenge is a lack of guidance from the federal government about what should be included in these plans and how to achieve goals and fund the efforts. Without this support, climate action plans result in a patchwork of efforts, he said.

Inflation Reduction Act

Despite these challenges, positive efforts are taking place. A critical achievement in addressing climate change is the federal Inflation Reduction Act, which became law in 2022. It includes the most significant climate legislation in U.S. history, Hodge said, and aims to move the nation to a clean energy economy. Billions of dollars have been dedicated to funding state, county and local governments in the effort.

It is vital that government entities have a staff person on hand who can apply for these federal funds to execute the climate action plan, Hodge said. “If (your community) is not pursuing those dollars, other communities will pursue those dollars and they will be gone at a certain point.”

Addressing policy and regulatory challenges is something social workers can get behind, he noted. “There is a space for all social workers to be involved in policy and political work. It’s in our Code of Ethics. We have an ethical obligation to engage in social and political action, social justice and equity.”

Even social workers who run private practices can help promote climate-positive initiatives, he said, such as offering pro bono work—and/or interacting with climate advocacy organizations like NASW and the Sierra Club. It helps to engage with your policymakers, and you should be aware of their policies, Hodge said. “If you live in a community that doesn’t have a climate action plan, it’s worth asking why not.”

One of the most important things social workers can do is encourage people to vote, he said.

“We can yell and scream about the Earth being on fire,” Hodge said, “but until we have elected officials who want to do something about it, there is not going to be much change.”

Tools for Resilience

Christina Erickson, PhD, LISW, professor and chairperson of Social Work and Environmental Studies at Augsburg University in Minneapolis, presented on “Climate Change: Social Work Tools for Resilience.”

She said she saw social work as her calling but was always active in promoting environmentally friendly activities like riding her bike or taking the bus to work. She said she realized the value of the knowledge base social workers have and how those skills can transform environmental justice. Climate change is the warming of the Earth, which has been scientifically proven, she said.

“Through that warming, we are experiencing things that are dangerous to us, like heat waves, tornadoes, winter storms, hurricanes, and, as a person who lives in a cold climate, there has been change,” Erickson said.

Another issue is land degradation or the loss of topsoil due to the expansion of human development. For example, concrete in urban areas traps heat. Climate change and land degradation are a threat to our financial stability, and our mental and physical health. It is especially felt by those who live in poverty, with underlying health conditions and other vulnerabilities, she said.

Resilience Matters

Rapid changes in social structures can make it difficult for children and families. Such changes impact people’s moods, which can include an increase in violence, depression, and anxiety, she said. People who are just beginning their lives are at risk of being climate refugees, she said.

“We are not (working) forward seven generations as our American Indian partners tell us we should be doing,” Erickson said. “We are not looking forward to our future and what we can offer our children. It does feel like we are putting our children in a risky position.”

She said crafting social change involves:

- Building community infrastructure for resiliencies

- The political will to change, a movement to support clean energy and regenerative land use systems

- Creating islands of change and resilience in organizations. Think about how organizations operate and how they can do things differently.

One way to do this is to “give a vote to nature” by proxy when it comes to making decisions that impact the environment, she said. Another example of institutional change is charging a “green fee.” It is a method to set aside funds to support environmental efforts for the natural and ecological systems around us.

Erickson said her university charges a nominal green fee per student each semester. It’s like a campus use fee, she said. These funds are distributed to the student government, which has an environmental action committee. She said other organizations can mirror the idea of charging a green fee.

“As social workers, we craft social change,” Erickson said. “That’s the fun of being a social worker. It’s such a great profession we are in. I can’t think of a job I would have loved more than being a social worker and trying to problem solve with other people about how to make the world a better place.”